Navigating public transportation in Berlin takes some getting used to. Taking the ferry and trains to reach the city was a pleasant roll through the sea and countryside which is also the exact opposite experience of Berlin’s Central Station. I wandered aimlessly through this five-level monstrosity where train tracks, escalators, and shopping met in an architectural Frankenstein. Several floors up were the local trains I needed to get out and to my apartment for the week. I made it the necessary few stops further east, got turned around at the last station, and took the right bus in the wrong direction. Disoriented and exhausted I finally made it to Alt-Treptow where I was all too happy to offload.

It took a couple of days to get my bearings and figure out what my priorities were in this city. Wandering among various memorials and museums gave me an idea of what my research options were and where I could find clues about our short but critical passage through Berlin. The beautiful thing about Berlin is that there are numerous foundations whose express purpose is the preservation of their troubled, local and national history. This made it easier to make a plan for the week, but first I had an interview appointment at one of the local radio stations.

Starting off the week with an on air talk about this project is a great motivator. I leisurely strolled through Kreuzberg and found my way to the offices of FluxFM, situated by the Spree river across from the East Side Gallery's sections of the wall. Foregoing the old and temperamental elevator, I climbed five flights of stairs to the top. It’s a good thing people can’t see you sweat on the radio.

My contact at the station found The Landless when we were still deep in crowdfunding stages and invited me to come in when I made it to Berlin. Hard to believe that was several months prior and now I was shaking hands with the staff while they made me fresh coffee. We talked and toured the offices, stepped out on the rooftop deck, and went over the interview plan. Moments later I was in the studio having a great conversation with the exuberant Charlie Winston. Following an introduction in German we talked entirely in English. My German language skills are passable but after 22 years of not practicing I’m much too rusty for intelligent dialogue.

It warmed my heart to have these people show such interest in my journey. We snapped photos, took down contact details, and said our goodbyes. I promised to return at some point for an update and left in high spirits. It was one of those moments when the long road of getting this far felt a little easier, a bit more worth it, and more rewarding. With renewed determination I began preparing for my next interview. But this time I would be on the other side of the mic.

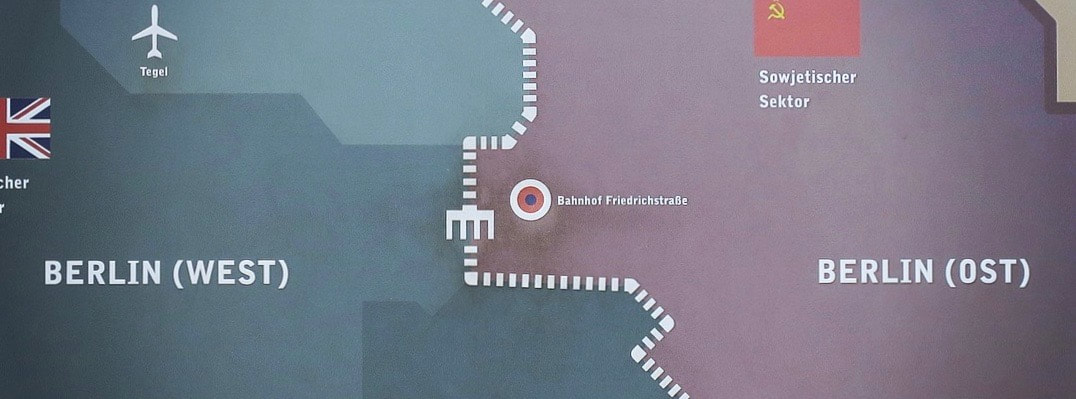

After some web sleuthing and asking around at the Berlin Wall Memorial, I was able to narrow down my search for the station that served as a border crossing between East and West Berlin. Bahnhof Friedrichstrasse, I was told, was the only place that trains were routed to and served as a traumatizing checkpoint for all those trying to move between the city’s two sides. If we came on a train, this would have had to be the place. Thing is, the stamps in our old passport didn’t quite make sense to me. There were two stamps from the DDR, what we used to call East Germany, and I couldn’t make sense of the dates on them. I would need some professional advice.

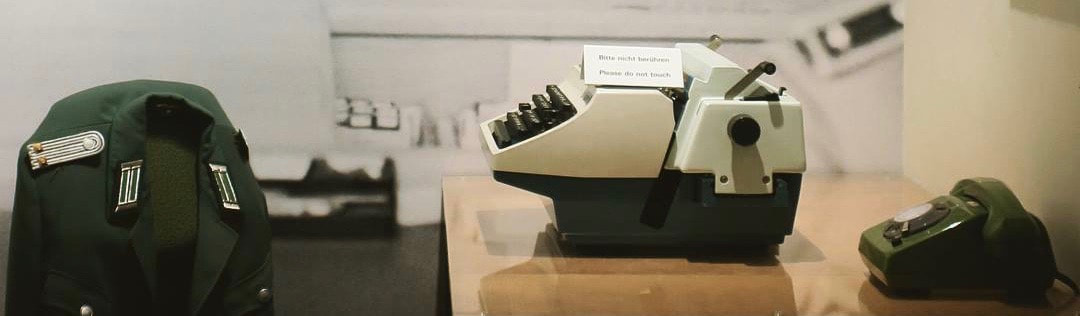

Paying a visit to the Tränenpalast museum was the next logical step. The station at Friedrichstrasse was a harrowing experience for a multitude of souls that passed through its maze-like corridors. Exacting scrutiny on the side of guards, inspecting belongings and documents while carrying automatic weapons, and pushing through train cars with German Shepherds were only some of the intimidation tactics used at what became commonly known as “the palace of tears.” And those are just the parts I remember. Walking through the museum, seeing the photos there, and listening to recordings, I was overwhelmed with feelings that I could not quite name. It was just a lot to take in and maybe I was responding to the staggering amount of lives that were affected here. I needed to take a moment and approach this with a fresh perspective, and some phone calls, in the morning.

Calling around the press offices of these museums I was able to get in touch with Dr. Mike Lukasch, director of both the Tränenpalast and the Museum in the Kulturbrauerei—another worthwhile stop for exhibits of daily work and life in the old DDR. He was very kind to not only make time for an interview, but also explain the meaning of our passport stamps and their various components.

Dr. Lukasch was invaluable in helping me understand the circumstances of how we got across the border. You see, for years we never understood how it was that we were even allowed to stay on a train we weren’t supposed to be on. And the next thing we knew, we were in the West. I can’t overstate the importance of that moment. The West was the other side. It was where you were free. The side which people died trying to reach before 1989. So us just rolling on through on a train was always a mystery, but now I had dates and station names to clear up some of that mystery. What still didn’t make sense, according to Dr. Lukasch, was that we had two entry stamps but no exit stamp. Very odd seeing as how there was no way to leave East Germany without that stamp of approval. But leave we did, and so the question of how exactly that happened remains.

We both looked at each other unsure of what truly happened on that train back in March of 1988. What we do know is that we were in fact at Friedrichstrasse station, and that something out of the ordinary happened to make our crossing possible. The train moved on to the next station in West Berlin, which has now been replaced by that abominable Central Station I got lost in, and we just stepped off the train car. We walked forward, afraid to look back, and gave all the money we had to a taxi driver who took us to a refugee camp in Spandau.

I spent the remainder of my time in Berlin looking for information about where this camp could have been located. Wondering if it was still there, maybe still in use. I called more museums and foundations. We even put out a request on air during the interview at FluxFM, but no luck. Everyone told me they didn’t know about a camp in Spandau. That it must have been the main refugee center in Berlin, at Marienfelde. I looked at the maps and photos, and I’m sure this wasn’t it. I distinctly remember it being by a canal and mom confirms it was in Spandau. Through an old friend of our family, who now lives in Berlin and works in government, I reached out to local offices in Spandau. I pressed for information among my various contacts as my time in Berlin was running out.

It would make for a great story if I could say that I found the camp in the nick of time but that’s not what happened. The trail ran cold and the nature of bureaucratic separation between institutions in Berlin meant that I was out of options. Time was up and I had bags to pack. The camp would just have to remain in memory. For now.